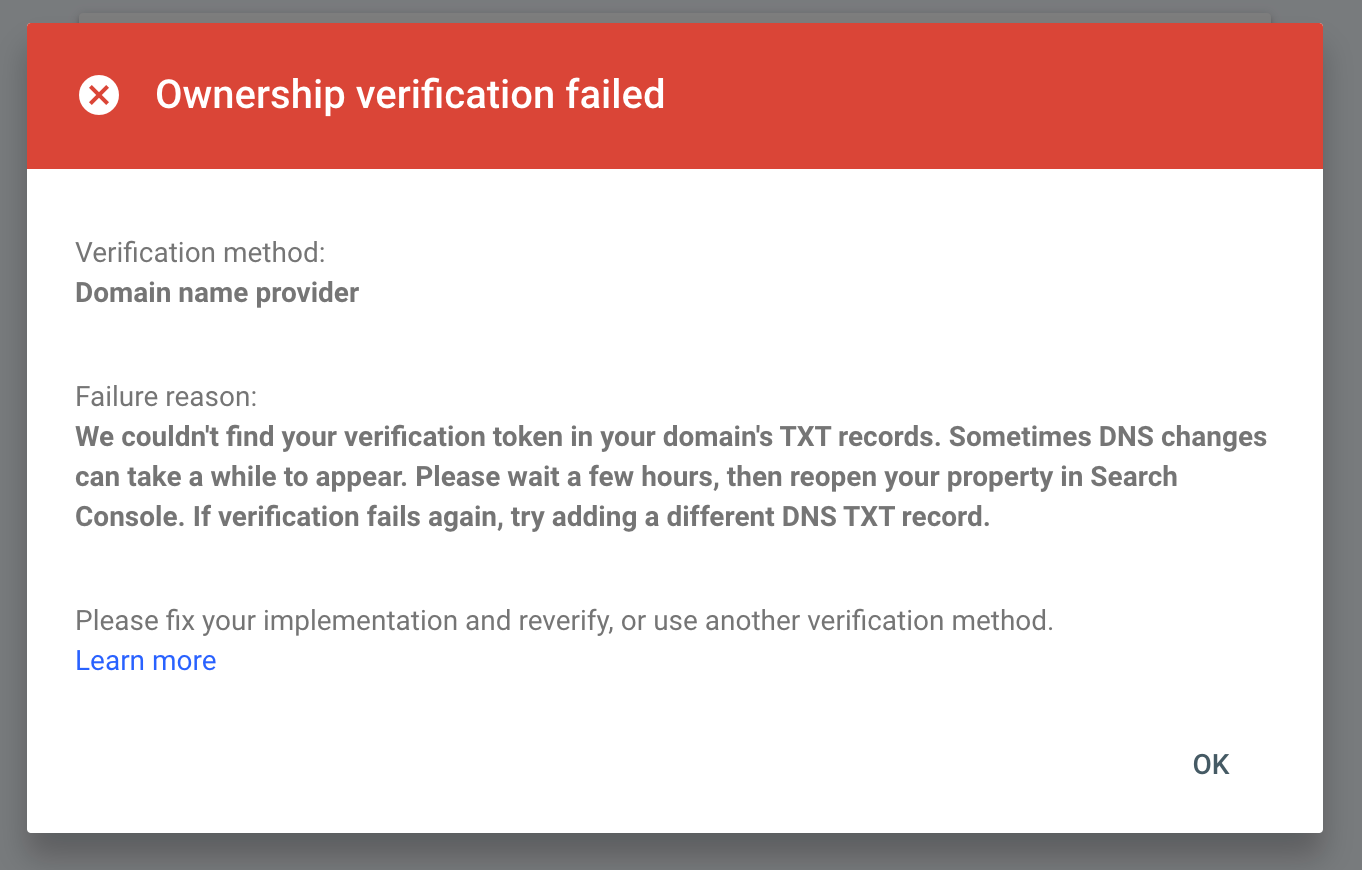

You add a DNS record. The app says it’s wrong. You check it, fix a typo, try again. Still wrong. You wait. You try again. Still wrong. You triple check it. It looks correct.

The app is checking DNS records in a half-assed way.

If you’re building a product that asks users to add DNS records, please take the time to verify DNS records properly.

Sometimes, users have to deal with DNS

Custom domains, email deliverability, domain ownership verification, and even Bluesky handles require users to add DNS records.

For example, if your product hosts web sites on custom domains, you might ask a user to add an A record for example.com pointing to 203.0.113.50 (your server’s IP).

This resolves example.com to your server’s IP, so browsers connect to your server, which can read the Host header and serve the appropriate site.

Surprisingly, users can add DNS records

Anyone who has asked users to add DNS records might be surprised to learn that many non-technical users can do it correctly with good instructions.

At the same time, even technical users sometimes struggle. Who will get stuck often depends on the quality of their provider’s DNS management interface.

Build a DNS verification feature

If your app asks users to add DNS records, give them a way to check for correctness.

A “verify DNS” button that tells the user immediately whether their record is correct or what’s wrong.

The user adds the record, clicks verify, and gets a definitive answer without having to wait for tech support to check and respond.

This is one of those features that has a huge payoff. It reduces tech support load and makes the whole experience less frustrating for everyone.

Bad solution: ask the cache

The simplest way to verify a DNS record is with a high level lookup function. In Go, that looks like this:

addrs, err := net.LookupHost("example.com")

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("lookup failed: %w", err)

}

if len(addrs) != 1 || addrs[0] != "203.0.113.50" {

return fmt.Errorf("expected 203.0.113.50, got %v", addrs)

}

This queries your server’s configured resolver, which almost certainly caches results. DNS records have a TTL (Time To Live) that specifies how long resolvers should cache them, but resolvers often ignore TTLs or enforce their own minimums. Even when TTLs are respected, the user’s record might have a TTL of 5 or 20 minutes. That’s a long time to make the user wait.

So the user adds their record, clicks verify, and your app checks the cache. The cache still has the old answer, or worse, a cached “not found” (NXDOMAIN). You tell the user it’s wrong. They double check. It looks right. They try again five minutes later. Still wrong. Now they’re frustrated and confused, second guessing themselves, when the record has been correct the whole time.

This is what some apps do and it actively makes the problem harder to debug.

Good solution: ask the authority

Instead of asking a cache, you can query the authoritative nameservers directly. These are the servers that actually hold the zone’s records.

At a high level, the code should look something like this:

nameservers := FindNameservers("example.com.")

for _, ns := range nameservers {

values := QueryServer(ns, "example.com.", dns.TypeA)

VerifyRecords(values, "203.0.113.50")

}

Find the nameservers

Query for NS records, walking up the domain tree until you find the zone’s nameservers:

func FindNameservers(fqdn string) ([]string, error) {

domain := fqdn

for {

msg := new(dns.Msg)

msg.SetQuestion(domain, dns.TypeNS)

msg.RecursionDesired = true

response, err := dns.Exchange(msg, "8.8.8.8:53")

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("NS lookup for %s: %w", domain, err)

}

var servers []string

for _, record := range response.Answer {

if ns, ok := record.(*dns.NS); ok {

servers = append(servers, ns.Ns)

}

}

if len(servers) > 0 {

return servers, nil

}

index := strings.Index(domain, ".")

if index < 0 {

break

}

next := domain[index+1:]

if next == "" || next == "." {

break

}

domain = next

}

return nil, fmt.Errorf("no nameservers found for %s", fqdn)

}

This starts with the full domain (e.g. sub.example.com.) and tries each parent zone until it finds one with NS records. Most domains will match on the first or second try.

Query each nameserver directly

Send your query directly to each nameserver. Since you’re asking the authoritative server, it answers from its own zone data, not a cache.

func QueryServer(server string, fqdn string, recordType uint16) ([]string, error) {

msg := new(dns.Msg)

msg.SetQuestion(fqdn, recordType)

// Some nameservers return empty answers for non-recursive queries.

msg.RecursionDesired = true

address := net.JoinHostPort(server, "53")

response, err := dns.Exchange(msg, address)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

var values []string

for _, record := range response.Answer {

switch r := record.(type) {

case *dns.A:

values = append(values, r.A.String())

case *dns.AAAA:

values = append(values, r.AAAA.String())

case *dns.CNAME:

values = append(values, r.Target)

case *dns.TXT:

values = append(values, strings.Join(r.Txt, ""))

case *dns.MX:

values = append(values, r.Mx)

}

}

return values, nil

}

Verify the response

This is where many implementations get it wrong. It’s not enough to check that the expected value is present in the response. You also need to check that it’s the only value.

func VerifyRecords(values []string, expected string) (bool, string) {

if len(values) == 0 {

return false, "no records found"

}

if len(values) > 1 {

return false, fmt.Sprintf("expected 1 record, got %d: %v", len(values), values)

}

got := strings.TrimSuffix(values[0], ".")

want := strings.TrimSuffix(expected, ".")

if !strings.EqualFold(got, want) {

return false, fmt.Sprintf("expected %s, got %s", want, got)

}

return true, ""

}

Watch out for extra records. Users sometimes add the correct record and leave an old one in place, or accidentally create duplicates. For example, a user adding an

Arecord with your IP might not realize they already have anArecord pointing somewhere else. The nameserver will return both values. If you only check that your expected value is present, you’ll tell the user everything looks good, but traffic will be split between two IPs and their site will break intermittently. Always verify that the response contains exactly the records you expect, nothing more.

Instant feedback

Authoritative verification gives users immediate, accurate results. They know right away if their record is correct, with no waiting for caches to expire and no guessing.

If you ask users to add DNS records, check them authoritatively, please!

An example in Go

I put together a small Go library and CLI tool called addled that wraps up the approach described in this post.

Find me on Bluesky

I am @jacob.gold on Bluesky. Always happy to chat!